Les Tortillards

There is something indefinably romantic about "tortillards" and Decauville products in particular. For me they are as evocative of France as Gauloises, street piesoirs and =snails. They represent an era now lost beyond reclaim, and relegated to that part of one's sub-conscious called nostalgia. Gauloises, for one reared on surreptitious smoking behind the school cricket pavilion on lazy summer afternoons, have now been adulterated and watered down beyond recognition. Street piusoira (of fond memory) have been swept away in a curious juxtaposition where public morality has been drastically relaxed and yet basic calls of nature are now coyly hidden in obscure, scarce and hard to find stainless steel and plastic emporium Snails I never did brave anyway, but I always enjoyed watching the early English package tourists pretend to enjoy them (washed down with tidal waves of plonk) so that they could brag back in the saloon bars at home. My interest in French narrow gauge locomotives was first awakened by an academically disastrous exchange visit to Brittany, where I spent a delightful summer near Carhaix with the family of a loco driver on the Reseau Breton, learning how to fire Mallet tanks, the names of all the loco pasty and how to swear in Breton. The writings of the late Dennis Allendun in 'Model Railway News' in the late fifties and early sixties, with their delightfully atmospheric drawings took this interest a stage further. Up through the high lonely lands of Central France there writhe(d) 44 miles of casual, twisted metre gauge track - the Tramways Departmentaux de la Correze. At one of the loneliest places on the line they built a junction and a depot and a station - a station so deeply buried in the green heart of a lost land that only the most rabid devotees seek it out. This is a pity, for it is everyone's idea of what a narrow gauge station should be like ... the local village was too small to justify exclusive ownership, so they threw in the next village a well, and called it Le MORTIER-GUMOND with Colin Binnie insisting on me re-christening my replica 'Le Mortier-Gourmand' after eating one of any sandwiches. My particular interest has always been small 0-4-0 tank locomotives, so when 1 first saw a Playcraft 009 Decauville locomotive in the local model shop, it was love at first sight. Hitherto, I had unswerving loyalty to small Welsh quarry locomotives, particularly the baby Hunslets, but now I determined to find out more. Enough of the personal bit - on with the history.

Armand Decauville founded his company in 1854 to build and repair distillery equipment. Working with the vintners, he and his son Paul became convinced that carriage over steel rails would be easier and quicker than the farm carts of the day on the muddy rural roads. They conceived the idea of light track of 400 and 500 mm gauge made in sections light enough for a man to carry. The rails were riveted to iron sleepers and diagonally opposite rails carried fishplates which held the sections together without bolts. This portable track could easily be laid into the fields where the harvest was taking place. Narrow gauge railways steam power were already in existence. The Ffestiniog Railway had demonstrated the use of steam on the 1' 11*" gauge in 1865 this had aroused interest all over Europe and the United States. Krauss built their first narrow gauge engine in 1868 and their first 500 mm gauge engine in 1871. The narrow gauges were not a new invention at the time Decauville was developing his ideas. What then was their contribution and why did the word Decauville come to be a common word for almost any sub-metric gang The narrow gauges from 500 to 800 mm (2' 7k") gauge in existence in the early 1870's were at mines and quarries where substantial tonnages of material were handled. They were no different than the tram roads which had existed from the late 1700's, except for gauge, and which developed into the early railways. The usual motive power was the horse and steam was a logical successor once the moll locomotive was proved practical. The essential point was that these lines had fixed rights-of-way and were permanent. The Decauville approach was portable track, easily laid and easily moved. Short lines with the cars pushed by hand or horse drawn could be installed almost anywhere and the track just laid on the ground. As their ideas for agricultural railways took shape, they saw other uses for this concept and naturally they also saw that for some of these uses small locomotives would be required. As you read the old catalogues, you have the feeling that they were carried away with their own enthusiasm. For example they list as potential uses:

Artillery support - carrying shells to the guns

Armies in the field

Exploration in Africa - carrying boats round rapids

Pier and wharf lines

Gas plants supply of coal to the ovens

Forges and machine shops

Sugar cane plantations - horse/mule/ox traction

Sugar cane plantations - steam traction

Public works/excavations - horse/hand/steam traction

Mines and quarries

Oyster farms

Coal briquette plants and cement plants

Sugar beet/potato/turnip farms

Sugar mills

Wine cellars

Forest lines

Factory to main line station lines

Inclines

In their 1894 catalogue, they devote 20 of the 100 pages to these uses and only on three of the pages do they mention locomotives all of the rest are based on hand or horse traction. Decauville's method of bringing their equipment to public attention was to exhibit at the expositions and agricultural shows of the day and their catalogue recites all of the prizes which they won. By 1894 they had sold the amazing quantity of 9,400 km of portable track to some 8,900 customers. From these figures it is obvious that the average line was only 1.05 km long. They had several major successes. In Australia the Colonial Sugar Refining Company purchased 53 km of track, six locomotives and several hundred cars. They supplied several hundred kilometres of track to the French Army for their North African wars. They had some notable failures. For the British Indian Army border war in Afghanistan, they supplied a 500 mm gauge 0-4-0 tank engine and tender. The locomotive was built so that the frame, cylinders and wheels could be detached from the boiler and these two pieces plus the tender carried by three elephants. Other elephants carried the portable track and cars. Needless to say the elephants were standard gauge and not supplied by Decauville: The accompanying illustration number "3" is from a 1916 Decauville catalogue and depicts this equipment. As part of their demonstrations at expositions they built in 1889, a passenger carrying 600 mm gauge line using Mallet type 0-4-4-0 tank engines. The accompanying illustration number "1° shows one of these locomotives, a Decauville Type No. 8 Mallet's Patent Compound Jointed Locomotive - actually built by Metallurgique for Decauville. They weighed 9.5 tons empty (12 tons in working order), wore designed to burn wood, coal or coke, and were able to ascend 8;6 gradients on curves of 20 to 35 metres radius with 19 lb rails (An absolutely excellent drawing of one of these locomotives by Fred Morris and to 16 mm/1 ft scale was published by the Narrow Gauge Railway Society as their Supplementary Drawing Sheet No. 8, issued with 'Narrow Gauge Illustrated' a few years back - NGI 65 Summer 1973).

In this period there was great interest in construe Ling tramways running alongside the country roads. The rural roads in Europe were muddy and full of holes and the transportation of people and farm produce to the market centres was slow indeed. Decauville built two lines to prove that the 600 mm gauge was suitable and in fact the best for this type of light railway. Their success was very limited for most of the subsequent lines were constructed to meter gauge. One of their lines, the Tramways de Pithiviers Toury, whose principal traffic was sugar beets, survived until 1964 - indirectly bequeathing one of its Alco 2-6-2T's to the Ffestiniog Railway. It is rather ironic that the Germans picked up the Decauville idea of 600 mm gauge military railways and developed it far beyond the French concepts. An interesting thing in the 1890 and 1894 catalogues is that they produced over 100 types of 400, 500 and 600 mm gauge cars. It leads to the conclusion that they virtually built to order and secured none of the advantages of mass production. Naturally, their approach attracted competitors. Bochum Verein and Arthur Koppel in Germany, Kerr Stuart and Robert Hudson in England and later H.K. Porter in the United States entered the same business. The British suppliers captured the markets in their colonial possessions and the Germans took the largest share of the European market and the export market where they could compete on price and delivery. Decauville was finally left with the French market and their colonial possessions none of which were as intensively developed as those under British influence. Decauville in the period from 1881 to 1928 produced something less than 1,800 locomotives which includes the 350 engines built for the French Artillery Service during World War 1. Their records were destroyed during World War 2 and thus a complete list of their engines with works numbers does not exist. Their construction numbers are in four series 1 to 1800 produced between 1877 and 1928. These are the engines sold to normal commercial customers and military engines. Then there are the 5000, 6000 and 7000 series. The 5000 and 6000 series were

There is something indefinably romantic about "tortillards" and Decauville products in particular. For me they are as evocative of France as Gauloises, street piesoirs and =snails. They represent an era now lost beyond reclaim, and relegated to that part of one's sub-conscious called nostalgia. Gauloises, for one reared on surreptitious smoking behind the school cricket pavilion on lazy summer afternoons, have now been adulterated and watered down beyond recognition. Street piusoira (of fond memory) have been swept away in a curious juxtaposition where public morality has been drastically relaxed and yet basic calls of nature are now coyly hidden in obscure, scarce and hard to find stainless steel and plastic emporium Snails I never did brave anyway, but I always enjoyed watching the early English package tourists pretend to enjoy them (washed down with tidal waves of plonk) so that they could brag back in the saloon bars at home. My interest in French narrow gauge locomotives was first awakened by an academically disastrous exchange visit to Brittany, where I spent a delightful summer near Carhaix with the family of a loco driver on the Reseau Breton, learning how to fire Mallet tanks, the names of all the loco pasty and how to swear in Breton. The writings of the late Dennis Allendun in 'Model Railway News' in the late fifties and early sixties, with their delightfully atmospheric drawings took this interest a stage further. Up through the high lonely lands of Central France there writhe(d) 44 miles of casual, twisted metre gauge track - the Tramways Departmentaux de la Correze. At one of the loneliest places on the line they built a junction and a depot and a station - a station so deeply buried in the green heart of a lost land that only the most rabid devotees seek it out. This is a pity, for it is everyone's idea of what a narrow gauge station should be like ... the local village was too small to justify exclusive ownership, so they threw in the next village a well, and called it Le MORTIER-GUMOND with Colin Binnie insisting on me re-christening my replica 'Le Mortier-Gourmand' after eating one of any sandwiches. My particular interest has always been small 0-4-0 tank locomotives, so when 1 first saw a Playcraft 009 Decauville locomotive in the local model shop, it was love at first sight. Hitherto, I had unswerving loyalty to small Welsh quarry locomotives, particularly the baby Hunslets, but now I determined to find out more. Enough of the personal bit - on with the history.

Armand Decauville founded his company in 1854 to build and repair distillery equipment. Working with the vintners, he and his son Paul became convinced that carriage over steel rails would be easier and quicker than the farm carts of the day on the muddy rural roads. They conceived the idea of light track of 400 and 500 mm gauge made in sections light enough for a man to carry. The rails were riveted to iron sleepers and diagonally opposite rails carried fishplates which held the sections together without bolts. This portable track could easily be laid into the fields where the harvest was taking place. Narrow gauge railways steam power were already in existence. The Ffestiniog Railway had demonstrated the use of steam on the 1' 11*" gauge in 1865 this had aroused interest all over Europe and the United States. Krauss built their first narrow gauge engine in 1868 and their first 500 mm gauge engine in 1871. The narrow gauges were not a new invention at the time Decauville was developing his ideas. What then was their contribution and why did the word Decauville come to be a common word for almost any sub-metric gang The narrow gauges from 500 to 800 mm (2' 7k") gauge in existence in the early 1870's were at mines and quarries where substantial tonnages of material were handled. They were no different than the tram roads which had existed from the late 1700's, except for gauge, and which developed into the early railways. The usual motive power was the horse and steam was a logical successor once the moll locomotive was proved practical. The essential point was that these lines had fixed rights-of-way and were permanent. The Decauville approach was portable track, easily laid and easily moved. Short lines with the cars pushed by hand or horse drawn could be installed almost anywhere and the track just laid on the ground. As their ideas for agricultural railways took shape, they saw other uses for this concept and naturally they also saw that for some of these uses small locomotives would be required. As you read the old catalogues, you have the feeling that they were carried away with their own enthusiasm. For example they list as potential uses:

Artillery support - carrying shells to the guns

Armies in the field

Exploration in Africa - carrying boats round rapids

Pier and wharf lines

Gas plants supply of coal to the ovens

Forges and machine shops

Sugar cane plantations - horse/mule/ox traction

Sugar cane plantations - steam traction

Public works/excavations - horse/hand/steam traction

Mines and quarries

Oyster farms

Coal briquette plants and cement plants

Sugar beet/potato/turnip farms

Sugar mills

Wine cellars

Forest lines

Factory to main line station lines

Inclines

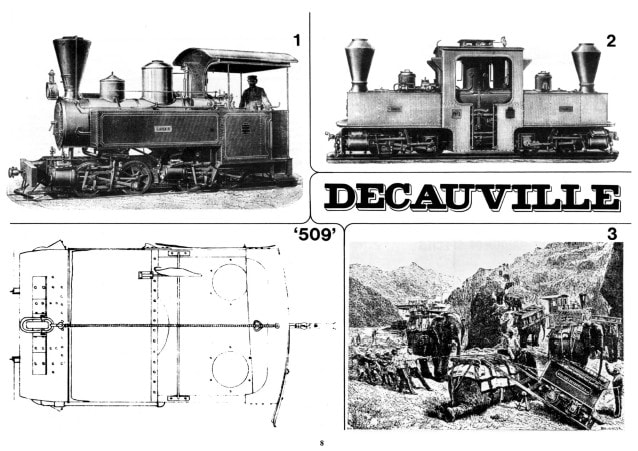

In their 1894 catalogue, they devote 20 of the 100 pages to these uses and only on three of the pages do they mention locomotives all of the rest are based on hand or horse traction. Decauville's method of bringing their equipment to public attention was to exhibit at the expositions and agricultural shows of the day and their catalogue recites all of the prizes which they won. By 1894 they had sold the amazing quantity of 9,400 km of portable track to some 8,900 customers. From these figures it is obvious that the average line was only 1.05 km long. They had several major successes. In Australia the Colonial Sugar Refining Company purchased 53 km of track, six locomotives and several hundred cars. They supplied several hundred kilometres of track to the French Army for their North African wars. They had some notable failures. For the British Indian Army border war in Afghanistan, they supplied a 500 mm gauge 0-4-0 tank engine and tender. The locomotive was built so that the frame, cylinders and wheels could be detached from the boiler and these two pieces plus the tender carried by three elephants. Other elephants carried the portable track and cars. Needless to say the elephants were standard gauge and not supplied by Decauville: The accompanying illustration number "3" is from a 1916 Decauville catalogue and depicts this equipment. As part of their demonstrations at expositions they built in 1889, a passenger carrying 600 mm gauge line using Mallet type 0-4-4-0 tank engines. The accompanying illustration number "1° shows one of these locomotives, a Decauville Type No. 8 Mallet's Patent Compound Jointed Locomotive - actually built by Metallurgique for Decauville. They weighed 9.5 tons empty (12 tons in working order), wore designed to burn wood, coal or coke, and were able to ascend 8;6 gradients on curves of 20 to 35 metres radius with 19 lb rails (An absolutely excellent drawing of one of these locomotives by Fred Morris and to 16 mm/1 ft scale was published by the Narrow Gauge Railway Society as their Supplementary Drawing Sheet No. 8, issued with 'Narrow Gauge Illustrated' a few years back - NGI 65 Summer 1973).

In this period there was great interest in construe Ling tramways running alongside the country roads. The rural roads in Europe were muddy and full of holes and the transportation of people and farm produce to the market centres was slow indeed. Decauville built two lines to prove that the 600 mm gauge was suitable and in fact the best for this type of light railway. Their success was very limited for most of the subsequent lines were constructed to meter gauge. One of their lines, the Tramways de Pithiviers Toury, whose principal traffic was sugar beets, survived until 1964 - indirectly bequeathing one of its Alco 2-6-2T's to the Ffestiniog Railway. It is rather ironic that the Germans picked up the Decauville idea of 600 mm gauge military railways and developed it far beyond the French concepts. An interesting thing in the 1890 and 1894 catalogues is that they produced over 100 types of 400, 500 and 600 mm gauge cars. It leads to the conclusion that they virtually built to order and secured none of the advantages of mass production. Naturally, their approach attracted competitors. Bochum Verein and Arthur Koppel in Germany, Kerr Stuart and Robert Hudson in England and later H.K. Porter in the United States entered the same business. The British suppliers captured the markets in their colonial possessions and the Germans took the largest share of the European market and the export market where they could compete on price and delivery. Decauville was finally left with the French market and their colonial possessions none of which were as intensively developed as those under British influence. Decauville in the period from 1881 to 1928 produced something less than 1,800 locomotives which includes the 350 engines built for the French Artillery Service during World War 1. Their records were destroyed during World War 2 and thus a complete list of their engines with works numbers does not exist. Their construction numbers are in four series 1 to 1800 produced between 1877 and 1928. These are the engines sold to normal commercial customers and military engines. Then there are the 5000, 6000 and 7000 series. The 5000 and 6000

Armand Decauville founded his company in 1854 to build and repair distillery equipment. Working with the vintners, he and his son Paul became convinced that carriage over steel rails would be easier and quicker than the farm carts of the day on the muddy rural roads. They conceived the idea of light track of 400 and 500 mm gauge made in sections light enough for a man to carry. The rails were riveted to iron sleepers and diagonally opposite rails carried fishplates which held the sections together without bolts. This portable track could easily be laid into the fields where the harvest was taking place. Narrow gauge railways steam power were already in existence. The Ffestiniog Railway had demonstrated the use of steam on the 1' 11*" gauge in 1865 this had aroused interest all over Europe and the United States. Krauss built their first narrow gauge engine in 1868 and their first 500 mm gauge engine in 1871. The narrow gauges were not a new invention at the time Decauville was developing his ideas. What then was their contribution and why did the word Decauville come to be a common word for almost any sub-metric gang The narrow gauges from 500 to 800 mm (2' 7k") gauge in existence in the early 1870's were at mines and quarries where substantial tonnages of material were handled. They were no different than the tram roads which had existed from the late 1700's, except for gauge, and which developed into the early railways. The usual motive power was the horse and steam was a logical successor once the moll locomotive was proved practical. The essential point was that these lines had fixed rights-of-way and were permanent. The Decauville approach was portable track, easily laid and easily moved. Short lines with the cars pushed by hand or horse drawn could be installed almost anywhere and the track just laid on the ground. As their ideas for agricultural railways took shape, they saw other uses for this concept and naturally they also saw that for some of these uses small locomotives would be required. As you read the old catalogues, you have the feeling that they were carried away with their own enthusiasm. For example they list as potential uses:

Artillery support - carrying shells to the guns

Armies in the field

Exploration in Africa - carrying boats round rapids

Pier and wharf lines

Gas plants supply of coal to the ovens

Forges and machine shops

Sugar cane plantations - horse/mule/ox traction

Sugar cane plantations - steam traction

Public works/excavations - horse/hand/steam traction

Mines and quarries

Oyster farms

Coal briquette plants and cement plants

Sugar beet/potato/turnip farms

Sugar mills

Wine cellars

Forest lines

Factory to main line station lines

Inclines

In their 1894 catalogue, they devote 20 of the 100 pages to these uses and only on three of the pages do they mention locomotives all of the rest are based on hand or horse traction. Decauville's method of bringing their equipment to public attention was to exhibit at the expositions and agricultural shows of the day and their catalogue recites all of the prizes which they won. By 1894 they had sold the amazing quantity of 9,400 km of portable track to some 8,900 customers. From these figures it is obvious that the average line was only 1.05 km long. They had several major successes. In Australia the Colonial Sugar Refining Company purchased 53 km of track, six locomotives and several hundred cars. They supplied several hundred kilometres of track to the French Army for their North African wars. They had some notable failures. For the British Indian Army border war in Afghanistan, they supplied a 500 mm gauge 0-4-0 tank engine and tender. The locomotive was built so that the frame, cylinders and wheels could be detached from the boiler and these two pieces plus the tender carried by three elephants. Other elephants carried the portable track and cars. Needless to say the elephants were standard gauge and not supplied by Decauville: The accompanying illustration number "3" is from a 1916 Decauville catalogue and depicts this equipment. As part of their demonstrations at expositions they built in 1889, a passenger carrying 600 mm gauge line using Mallet type 0-4-4-0 tank engines. The accompanying illustration number "1° shows one of these locomotives, a Decauville Type No. 8 Mallet's Patent Compound Jointed Locomotive - actually built by Metallurgique for Decauville. They weighed 9.5 tons empty (12 tons in working order), wore designed to burn wood, coal or coke, and were able to ascend 8;6 gradients on curves of 20 to 35 metres radius with 19 lb rails (An absolutely excellent drawing of one of these locomotives by Fred Morris and to 16 mm/1 ft scale was published by the Narrow Gauge Railway Society as their Supplementary Drawing Sheet No. 8, issued with 'Narrow Gauge Illustrated' a few years back - NGI 65 Summer 1973).

In this period there was great interest in construe Ling tramways running alongside the country roads. The rural roads in Europe were muddy and full of holes and the transportation of people and farm produce to the market centres was slow indeed. Decauville built two lines to prove that the 600 mm gauge was suitable and in fact the best for this type of light railway. Their success was very limited for most of the subsequent lines were constructed to meter gauge. One of their lines, the Tramways de Pithiviers Toury, whose principal traffic was sugar beets, survived until 1964 - indirectly bequeathing one of its Alco 2-6-2T's to the Ffestiniog Railway. It is rather ironic that the Germans picked up the Decauville idea of 600 mm gauge military railways and developed it far beyond the French concepts. An interesting thing in the 1890 and 1894 catalogues is that they produced over 100 types of 400, 500 and 600 mm gauge cars. It leads to the conclusion that they virtually built to order and secured none of the advantages of mass production. Naturally, their approach attracted competitors. Bochum Verein and Arthur Koppel in Germany, Kerr Stuart and Robert Hudson in England and later H.K. Porter in the United States entered the same business. The British suppliers captured the markets in their colonial possessions and the Germans took the largest share of the European market and the export market where they could compete on price and delivery. Decauville was finally left with the French market and their colonial possessions none of which were as intensively developed as those under British influence. Decauville in the period from 1881 to 1928 produced something less than 1,800 locomotives which includes the 350 engines built for the French Artillery Service during World War 1. Their records were destroyed during World War 2 and thus a complete list of their engines with works numbers does not exist. Their construction numbers are in four series 1 to 1800 produced between 1877 and 1928. These are the engines sold to normal commercial customers and military engines. Then there are the 5000, 6000 and 7000 series. The 5000 and 6000 series were

There is something indefinably romantic about "tortillards" and Decauville products in particular. For me they are as evocative of France as Gauloises, street piesoirs and =snails. They represent an era now lost beyond reclaim, and relegated to that part of one's sub-conscious called nostalgia. Gauloises, for one reared on surreptitious smoking behind the school cricket pavilion on lazy summer afternoons, have now been adulterated and watered down beyond recognition. Street piusoira (of fond memory) have been swept away in a curious juxtaposition where public morality has been drastically relaxed and yet basic calls of nature are now coyly hidden in obscure, scarce and hard to find stainless steel and plastic emporium Snails I never did brave anyway, but I always enjoyed watching the early English package tourists pretend to enjoy them (washed down with tidal waves of plonk) so that they could brag back in the saloon bars at home. My interest in French narrow gauge locomotives was first awakened by an academically disastrous exchange visit to Brittany, where I spent a delightful summer near Carhaix with the family of a loco driver on the Reseau Breton, learning how to fire Mallet tanks, the names of all the loco pasty and how to swear in Breton. The writings of the late Dennis Allendun in 'Model Railway News' in the late fifties and early sixties, with their delightfully atmospheric drawings took this interest a stage further. Up through the high lonely lands of Central France there writhe(d) 44 miles of casual, twisted metre gauge track - the Tramways Departmentaux de la Correze. At one of the loneliest places on the line they built a junction and a depot and a station - a station so deeply buried in the green heart of a lost land that only the most rabid devotees seek it out. This is a pity, for it is everyone's idea of what a narrow gauge station should be like ... the local village was too small to justify exclusive ownership, so they threw in the next village a well, and called it Le MORTIER-GUMOND with Colin Binnie insisting on me re-christening my replica 'Le Mortier-Gourmand' after eating one of any sandwiches. My particular interest has always been small 0-4-0 tank locomotives, so when 1 first saw a Playcraft 009 Decauville locomotive in the local model shop, it was love at first sight. Hitherto, I had unswerving loyalty to small Welsh quarry locomotives, particularly the baby Hunslets, but now I determined to find out more. Enough of the personal bit - on with the history.

Armand Decauville founded his company in 1854 to build and repair distillery equipment. Working with the vintners, he and his son Paul became convinced that carriage over steel rails would be easier and quicker than the farm carts of the day on the muddy rural roads. They conceived the idea of light track of 400 and 500 mm gauge made in sections light enough for a man to carry. The rails were riveted to iron sleepers and diagonally opposite rails carried fishplates which held the sections together without bolts. This portable track could easily be laid into the fields where the harvest was taking place. Narrow gauge railways steam power were already in existence. The Ffestiniog Railway had demonstrated the use of steam on the 1' 11*" gauge in 1865 this had aroused interest all over Europe and the United States. Krauss built their first narrow gauge engine in 1868 and their first 500 mm gauge engine in 1871. The narrow gauges were not a new invention at the time Decauville was developing his ideas. What then was their contribution and why did the word Decauville come to be a common word for almost any sub-metric gang The narrow gauges from 500 to 800 mm (2' 7k") gauge in existence in the early 1870's were at mines and quarries where substantial tonnages of material were handled. They were no different than the tram roads which had existed from the late 1700's, except for gauge, and which developed into the early railways. The usual motive power was the horse and steam was a logical successor once the moll locomotive was proved practical. The essential point was that these lines had fixed rights-of-way and were permanent. The Decauville approach was portable track, easily laid and easily moved. Short lines with the cars pushed by hand or horse drawn could be installed almost anywhere and the track just laid on the ground. As their ideas for agricultural railways took shape, they saw other uses for this concept and naturally they also saw that for some of these uses small locomotives would be required. As you read the old catalogues, you have the feeling that they were carried away with their own enthusiasm. For example they list as potential uses:

Artillery support - carrying shells to the guns

Armies in the field

Exploration in Africa - carrying boats round rapids

Pier and wharf lines

Gas plants supply of coal to the ovens

Forges and machine shops

Sugar cane plantations - horse/mule/ox traction

Sugar cane plantations - steam traction

Public works/excavations - horse/hand/steam traction

Mines and quarries

Oyster farms

Coal briquette plants and cement plants

Sugar beet/potato/turnip farms

Sugar mills

Wine cellars

Forest lines

Factory to main line station lines

Inclines

In their 1894 catalogue, they devote 20 of the 100 pages to these uses and only on three of the pages do they mention locomotives all of the rest are based on hand or horse traction. Decauville's method of bringing their equipment to public attention was to exhibit at the expositions and agricultural shows of the day and their catalogue recites all of the prizes which they won. By 1894 they had sold the amazing quantity of 9,400 km of portable track to some 8,900 customers. From these figures it is obvious that the average line was only 1.05 km long. They had several major successes. In Australia the Colonial Sugar Refining Company purchased 53 km of track, six locomotives and several hundred cars. They supplied several hundred kilometres of track to the French Army for their North African wars. They had some notable failures. For the British Indian Army border war in Afghanistan, they supplied a 500 mm gauge 0-4-0 tank engine and tender. The locomotive was built so that the frame, cylinders and wheels could be detached from the boiler and these two pieces plus the tender carried by three elephants. Other elephants carried the portable track and cars. Needless to say the elephants were standard gauge and not supplied by Decauville: The accompanying illustration number "3" is from a 1916 Decauville catalogue and depicts this equipment. As part of their demonstrations at expositions they built in 1889, a passenger carrying 600 mm gauge line using Mallet type 0-4-4-0 tank engines. The accompanying illustration number "1° shows one of these locomotives, a Decauville Type No. 8 Mallet's Patent Compound Jointed Locomotive - actually built by Metallurgique for Decauville. They weighed 9.5 tons empty (12 tons in working order), wore designed to burn wood, coal or coke, and were able to ascend 8;6 gradients on curves of 20 to 35 metres radius with 19 lb rails (An absolutely excellent drawing of one of these locomotives by Fred Morris and to 16 mm/1 ft scale was published by the Narrow Gauge Railway Society as their Supplementary Drawing Sheet No. 8, issued with 'Narrow Gauge Illustrated' a few years back - NGI 65 Summer 1973).

In this period there was great interest in construe Ling tramways running alongside the country roads. The rural roads in Europe were muddy and full of holes and the transportation of people and farm produce to the market centres was slow indeed. Decauville built two lines to prove that the 600 mm gauge was suitable and in fact the best for this type of light railway. Their success was very limited for most of the subsequent lines were constructed to meter gauge. One of their lines, the Tramways de Pithiviers Toury, whose principal traffic was sugar beets, survived until 1964 - indirectly bequeathing one of its Alco 2-6-2T's to the Ffestiniog Railway. It is rather ironic that the Germans picked up the Decauville idea of 600 mm gauge military railways and developed it far beyond the French concepts. An interesting thing in the 1890 and 1894 catalogues is that they produced over 100 types of 400, 500 and 600 mm gauge cars. It leads to the conclusion that they virtually built to order and secured none of the advantages of mass production. Naturally, their approach attracted competitors. Bochum Verein and Arthur Koppel in Germany, Kerr Stuart and Robert Hudson in England and later H.K. Porter in the United States entered the same business. The British suppliers captured the markets in their colonial possessions and the Germans took the largest share of the European market and the export market where they could compete on price and delivery. Decauville was finally left with the French market and their colonial possessions none of which were as intensively developed as those under British influence. Decauville in the period from 1881 to 1928 produced something less than 1,800 locomotives which includes the 350 engines built for the French Artillery Service during World War 1. Their records were destroyed during World War 2 and thus a complete list of their engines with works numbers does not exist. Their construction numbers are in four series 1 to 1800 produced between 1877 and 1928. These are the engines sold to normal commercial customers and military engines. Then there are the 5000, 6000 and 7000 series. The 5000 and 6000

series were built by German builders for Decauville and numbered in the manufacturer's own series, the 7000 series were standard gauge engine, A photo of 5022 which has a non-standard Decauville builders plate giving a date of 1913 is a standard Orenstein and Koppel design When Decauville first introduced locomotives, they had no manufacturing facilities and so they invited Cail and Couillet to disp locomotives. Nearly all of their subsequent locomotives came from Couillet whose full title is Usines Metallurgiques de Hainault Couillet. A total of 56 Decauville engines wore built by Couillet, all but 6 of Decauville's total sales between 1877 and

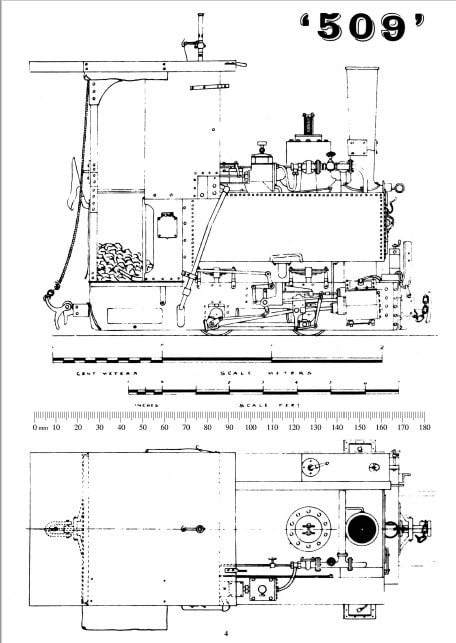

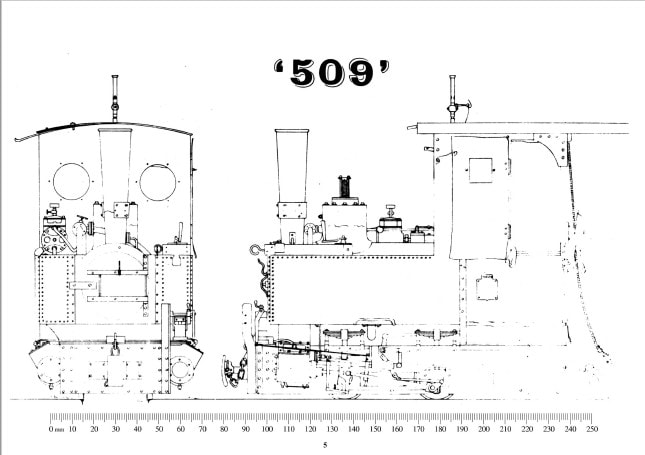

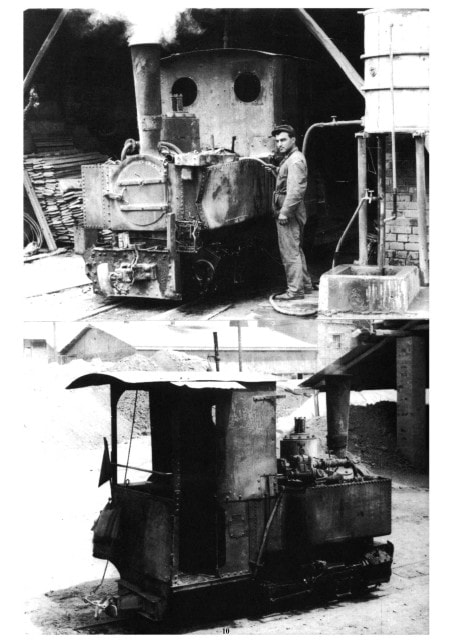

Works number 1, listed in their 1901 catalogue, was a tiny 0-4-0T named LILLIPUT. It weighed 1 1/4 tons and was built by Corpet Louvet to 500 mm gauge in 1878. Couillet was a Belgian company. We know that another Belgian company Les Ateliers Metallurgiaues Tubize built most of the Decauville Mallet type engines. Decauville's first engines were very small. The smallest standard was t. 0-4-0 type which in the tank version weighed 3 tons empty and 4 tons in working order. It is one of these locomotives No. 509 which features on this month’s front cover, and inside as plans and on the photopage. The tender version weights were 2 3/4 4 1/2 tons. The next size engine in the tank engine version weighed 4 tons empty and 6 tons in operating condition. A modification this design had weights of 6 and 75 tons. There were two designs which had a weight of 9i tons empty and 12 tons in operating condition, the 0-4-4-OT Mallet and the 0-4-04-0-4-0T Pechot-Bourdon design adopted by the French Army for their artillery railway. The accompanying illustration number "2" shows one of these Fairlie-type locomotives, a Decauville Type No, 9 Duplex

Locomotive. They able to run over curves of 20 to 35 meters radius and ascend 8% gradients with 19 lb rails. Later on they developed a 0-6-2T type whose weights were 10 and 13 tons. An interesting exercise for the historian is to try and match the Couillet list of engines built for Decauville with the Decauville list in their 1901 catalogue. Only for particular engines where there is some outstanding feature can the matching be done with any degree of accuracy. Until 1877 the number of engines Couille built corresponds fairly closely with the number of engines listed by Decauville. From 1887 on there is a wide discrepancy and this would indicate that about 1886-7 Decauville commenced their own production at Petit-Bourg. They still purchased locomotives. Decauville construction numbers (C/N) 93 and 94, 700 mm gauge 0-4-4-0T Mallet type were built by Tubize in 1890. In the early days Decauville evidently had locomotives built for stock and kept them until sold. This is clear from the early catalogues. In the 1897 catalogue it shows:

For Sale at Petit-Bourg C/N 29, 33, 66, 87, 133, 146, 150, 157 and 160;

Under Construction at Petit-Bourg C/N 76, 114, 166, 173 and the last engine listed is C/N 176.

By the time they issued their 1901 catalogue all of these had been sold except the two rack engines 157 and 160. Their one venture into compressed air locomotives C/N 29 gives an insight into their early operations. It was built by Couillet in 1881 and stayed at Petit-Bourg. in 1883/4, they gave it a works or construction number which was 29. By 1894 it was still unsold. Between 1094 and 1901 they finally sold it to a contractor, Mr. Chagnaud. Decauville's builders plates never showed the date and the rails must have been the practice of building for stock. The absence of a date on the builder’s plate makes the reconstruction of a builders list from known locomotives a difficult task. Another interesting question is raised by Decauville's purchase of all it early engines. It is common to speak of the "Decauville type" Locomotive. Usually this means a Belpaire boiler, outside frames, Walschaerts valve gear and other features common to all of their 0-4-0 and 0-6-2 type engines. However, if you examine a Hainaut Couillet 600 mm gauge engine of the same general time period, you will find all of the so-called Decauville characteristics. In other words it appears that Hainault/Couillet supplied Decauville with its standard design.

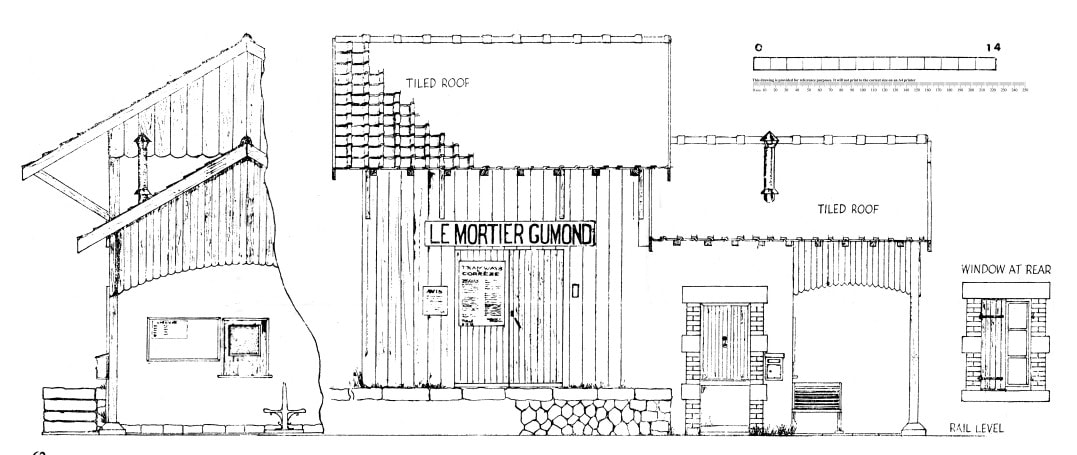

Enough of Decauville for a while, though I shall return to them later in this article. One of the other featured 16 mm/1 ft scale drawings in this issue is of LE MORTIER-GUMOND by Dennis Allenden, which first appeared in 'Model Railway News' for March 1959, on pages 62 to 65, together with a supporting article on building a 7 mm/1 ft scale model of the station.

Works number 1, listed in their 1901 catalogue, was a tiny 0-4-0T named LILLIPUT. It weighed 1 1/4 tons and was built by Corpet Louvet to 500 mm gauge in 1878. Couillet was a Belgian company. We know that another Belgian company Les Ateliers Metallurgiaues Tubize built most of the Decauville Mallet type engines. Decauville's first engines were very small. The smallest standard was t. 0-4-0 type which in the tank version weighed 3 tons empty and 4 tons in working order. It is one of these locomotives No. 509 which features on this month’s front cover, and inside as plans and on the photopage. The tender version weights were 2 3/4 4 1/2 tons. The next size engine in the tank engine version weighed 4 tons empty and 6 tons in operating condition. A modification this design had weights of 6 and 75 tons. There were two designs which had a weight of 9i tons empty and 12 tons in operating condition, the 0-4-4-OT Mallet and the 0-4-04-0-4-0T Pechot-Bourdon design adopted by the French Army for their artillery railway. The accompanying illustration number "2" shows one of these Fairlie-type locomotives, a Decauville Type No, 9 Duplex

Locomotive. They able to run over curves of 20 to 35 meters radius and ascend 8% gradients with 19 lb rails. Later on they developed a 0-6-2T type whose weights were 10 and 13 tons. An interesting exercise for the historian is to try and match the Couillet list of engines built for Decauville with the Decauville list in their 1901 catalogue. Only for particular engines where there is some outstanding feature can the matching be done with any degree of accuracy. Until 1877 the number of engines Couille built corresponds fairly closely with the number of engines listed by Decauville. From 1887 on there is a wide discrepancy and this would indicate that about 1886-7 Decauville commenced their own production at Petit-Bourg. They still purchased locomotives. Decauville construction numbers (C/N) 93 and 94, 700 mm gauge 0-4-4-0T Mallet type were built by Tubize in 1890. In the early days Decauville evidently had locomotives built for stock and kept them until sold. This is clear from the early catalogues. In the 1897 catalogue it shows:

For Sale at Petit-Bourg C/N 29, 33, 66, 87, 133, 146, 150, 157 and 160;

Under Construction at Petit-Bourg C/N 76, 114, 166, 173 and the last engine listed is C/N 176.

By the time they issued their 1901 catalogue all of these had been sold except the two rack engines 157 and 160. Their one venture into compressed air locomotives C/N 29 gives an insight into their early operations. It was built by Couillet in 1881 and stayed at Petit-Bourg. in 1883/4, they gave it a works or construction number which was 29. By 1894 it was still unsold. Between 1094 and 1901 they finally sold it to a contractor, Mr. Chagnaud. Decauville's builders plates never showed the date and the rails must have been the practice of building for stock. The absence of a date on the builder’s plate makes the reconstruction of a builders list from known locomotives a difficult task. Another interesting question is raised by Decauville's purchase of all it early engines. It is common to speak of the "Decauville type" Locomotive. Usually this means a Belpaire boiler, outside frames, Walschaerts valve gear and other features common to all of their 0-4-0 and 0-6-2 type engines. However, if you examine a Hainaut Couillet 600 mm gauge engine of the same general time period, you will find all of the so-called Decauville characteristics. In other words it appears that Hainault/Couillet supplied Decauville with its standard design.

Enough of Decauville for a while, though I shall return to them later in this article. One of the other featured 16 mm/1 ft scale drawings in this issue is of LE MORTIER-GUMOND by Dennis Allenden, which first appeared in 'Model Railway News' for March 1959, on pages 62 to 65, together with a supporting article on building a 7 mm/1 ft scale model of the station.

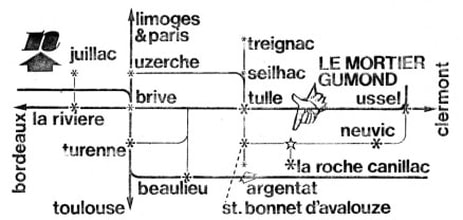

Thinking a little background information on the railway which served Le Mortier-Gumond might not go amiss, here goes.

TRAMWAYS DEPARTEMENTAUX DE LA COREZE

Lines: Tulle - St. Bonnet d'Avalouze - Le Mortier-Gumond Neuvic d'Ussel - Ussel (101 km).

Branch: Le Mortier-Gumond - La Roche Canillac 4.5 km).

Beaulieu/Turenne - Tulle.

La Riviere Juillac.

The Tramways Departementaux de la Correze were a relative latecomer on the French light railway scene and had a very short life. The company's ambitious plans were cut short by the First World War with 119.5 km of lines in operation and further extensions surveyed, all but one branch being closed within 22 years of the cutting of the first sod in 1912. Even in their heyday, traffic on most of the routes was negligible and there exists a most pathetic picture of the little terminus of Beaulieu, only a year or so after it had opened, with weeds sprouting between the tracks and a general air of poverty about it. The Tulle - Neuvic line, on which Le Mortier-Gumond was located, was the last survivor of this Departmental system comprising three isolated lines, two of them with branches. Its history is typical of Departmental concerns. The original concession was taken up by the Compagnie des Tramways Departementaux de la Correze (T.C.) who ran it from opening in 1912 until 1925 when the Departmental authorities bought it back and leased it to a P.O. subsidiary, the 95 km. Lignes de la Correze. In this fashion it passed thence to the Societe des Transports Auxiliares du P.O.(S.T.A.P.O.) in 1932 and thence in 1942 to the equivalent of the nationalised S.N.C.F., being the S.C.E.T.A. By this time it was the only line still being worked, and had already lost its branch to to La Roche Canillac in 1939. In 1946 the Neuvic to Ussel section was threatened by a new hydro-electric scheme at Doustres, but was saved at the expense of a 5 km long deviation, which included a long steel viaduct across the new lake. Ironically enough, this was the next section to go, being closed to all traffic in 1952. Unfortunately, the line had two disadvantages; it did not tap nearly enough traffic to pay for its upkeep; and it was never properly modernised. No diesel tractors replaced the ageing Piguets, experiments with railcars were half-hearted, and the track received. little attention. In consequence by 1959 things had got into such a state that not even two Billard railcars, rather belatedly purchased from the Pas de Calais system of the old V.P.I.L., could save it; the track was so bad that their potential could not be realised. So on January 1 st, 1960 it closed for good. By August, the track had been lifted and all remaining stock was stored at St. Bonnet d'Avalouse, waiting for the breakers torch. In the event it rotted there for another four years, with only one locomotive escaping to a preserved line.

Locomotives at closure were: Nos. 3, 4, 7, 8, 9 0-6-0T Piguet of 1905 weighing 18 tonnes,

formerly also Nos. 5, 6, (identical) and 13, 14, 17, (17 tonnes)

Railcars Originally (1928-on); Two Saurer, 6-w railcars; Two Tartery, 4-w railcars (scr.) Two De Dion, 4-w.

Introduced by S.C.E.T.A.; Three Be Dion ML type;

Two Billard 80 h.p. Bogie railcars.

TRAMWAYS DEPARTEMENTAUX DE LA COREZE

Lines: Tulle - St. Bonnet d'Avalouze - Le Mortier-Gumond Neuvic d'Ussel - Ussel (101 km).

Branch: Le Mortier-Gumond - La Roche Canillac 4.5 km).

Beaulieu/Turenne - Tulle.

La Riviere Juillac.

The Tramways Departementaux de la Correze were a relative latecomer on the French light railway scene and had a very short life. The company's ambitious plans were cut short by the First World War with 119.5 km of lines in operation and further extensions surveyed, all but one branch being closed within 22 years of the cutting of the first sod in 1912. Even in their heyday, traffic on most of the routes was negligible and there exists a most pathetic picture of the little terminus of Beaulieu, only a year or so after it had opened, with weeds sprouting between the tracks and a general air of poverty about it. The Tulle - Neuvic line, on which Le Mortier-Gumond was located, was the last survivor of this Departmental system comprising three isolated lines, two of them with branches. Its history is typical of Departmental concerns. The original concession was taken up by the Compagnie des Tramways Departementaux de la Correze (T.C.) who ran it from opening in 1912 until 1925 when the Departmental authorities bought it back and leased it to a P.O. subsidiary, the 95 km. Lignes de la Correze. In this fashion it passed thence to the Societe des Transports Auxiliares du P.O.(S.T.A.P.O.) in 1932 and thence in 1942 to the equivalent of the nationalised S.N.C.F., being the S.C.E.T.A. By this time it was the only line still being worked, and had already lost its branch to to La Roche Canillac in 1939. In 1946 the Neuvic to Ussel section was threatened by a new hydro-electric scheme at Doustres, but was saved at the expense of a 5 km long deviation, which included a long steel viaduct across the new lake. Ironically enough, this was the next section to go, being closed to all traffic in 1952. Unfortunately, the line had two disadvantages; it did not tap nearly enough traffic to pay for its upkeep; and it was never properly modernised. No diesel tractors replaced the ageing Piguets, experiments with railcars were half-hearted, and the track received. little attention. In consequence by 1959 things had got into such a state that not even two Billard railcars, rather belatedly purchased from the Pas de Calais system of the old V.P.I.L., could save it; the track was so bad that their potential could not be realised. So on January 1 st, 1960 it closed for good. By August, the track had been lifted and all remaining stock was stored at St. Bonnet d'Avalouse, waiting for the breakers torch. In the event it rotted there for another four years, with only one locomotive escaping to a preserved line.

Locomotives at closure were: Nos. 3, 4, 7, 8, 9 0-6-0T Piguet of 1905 weighing 18 tonnes,

formerly also Nos. 5, 6, (identical) and 13, 14, 17, (17 tonnes)

Railcars Originally (1928-on); Two Saurer, 6-w railcars; Two Tartery, 4-w railcars (scr.) Two De Dion, 4-w.

Introduced by S.C.E.T.A.; Three Be Dion ML type;

Two Billard 80 h.p. Bogie railcars.

Back to Decauville again. That Ale firm became so well established by the end of the nineteenth century was largely due to the successful and widespread use made of their products at the great Paris exhibition of 1889, although the previous exhibition of 1878 had set the firm on its feet by awarding Armand Decauville four gold and silver medals for his development, of light agricultural railways. The Exhibition, open from 6th May to 31st October and somewhat on the lines of our own Great Exhibition of 1851, was of all types of exhibits ranging through machinery and agriculture to the War Department and was extensively laid out in separate pavilions close to the River Seine. "Distances are very formidable and the most indefatigable visitor may be excused for dreading the long walk necessary for taking him from one centre of attraction to another". It was decided therefore early in the planning of the Exhibition that a railway should be constructed both to convey visitors around the displays and also as an exhibit in itself. Originally a circular route had been proposed which would have taken in the Avenue de la Motte-Picquet and Place des Iuvalides, then turning down the Rue Constantine towards the Foreign Office. It was decided, however, that this would prove too costly to construct, would interfere with public traffic and would be of comparatively little service to visitors so this was curtailed to make an eventual route of about two miles in length. Starting from the terminal station, known as the Gare de la Concorde, the railway traversed the width of the Esplanade des Invalides and passed onto the Quai d'Orsay at the back of the Agricultural Galleries and between an avenue of trees. The Agricultural Gallery Station at the Meier Crossroads was reached after crossing the Avenue de la Tour-Maubourg on the level. The gradient then fell to enable the line to pass through a tunnel under the junction of the Rapp and Bosquet Avenues and then rose to the third station opposite the Food Products building. The Avenue de la Bourdonnais was crossed on the level and then the line fell into a cutting in the Champ de mars in front of the Eiffel Tower. Just beyond the tower the fourth station was reached and then the line turned round onto the Avenue Suffren which it followed as far as the terminal station near the Avenue de la Motte Picquet. Details of the line may be summarized as follows:

Gauge: 600m Maximum Train Length: 165 feet

Steepest Gradient: 1 in 40 for 300 feet

Fare: 25 centimes for any distance

Minimum Curve: radius 131 feet (on sidings reduced to 65 ft 7 ins) Frequency of Service: every 10 minutes from 09.00 hrs to closing time.

Maximum Speed: 10 mph (reduced to 2 mph on level crossings)

Track: the steel rail was of 19 lbs/yard riveted to dished steel sleepers spaced about two feet apart. Complete sections of track were riveted together into lengths of about 16 1/2 feet at the Petit-Bourg works and needed only to be fishplated together at the Exhibition site and then laid well embedded in ballast. This permanent way was designed to carry a working load of three tons per axle.

Rolling Stock: It was considered that fifteen locomotives and one hundred carriages would be sufficient to run the 180 trains per day and in addition a number of wagons were specially constructed to assist in the erection of that Exhibition.

Locomotives: Prior to the Exhibition about 70 locomotives had been 'built' by Decauville. For the Exhibition ten (one source says seven) compound locomotives on the Mallet system were built and the names given to these referred to various applications of the Decauville system of railways. For example the TURKESTAN referred to 60 miles of line constructed in 1882 for temporary purposes in building the Transcaspian Railway, the AFGANISTAN commemorated the elephant line already mentioned, the MASSOUAH was named after a large order given by the Italian Government during the Abyssinian campaign, the AUSTRALIA as a complement to the Australian sugar making companies, and the MADAGASCAR and HANOI refer to lines laid down by the French Government. In addition it was intended that five other locomotives were to be used consisting of the 0-4-0+0-4-OT Pechot-Bourdon type and standard 4 ton empty Tank types. However no firm evidence has come to light that those latter types were in fact used. The 75 hp Mallet was the standard engine being 'built' by the firm at the time. On a straight level track it was capable of hauling 280 ton and this fell to 17 tons by a 1 in 15 gradient. The first Decauville-built Mallet had been exhibited the previous year at the concours Regional de Laon where a 600 mm line had first been demonstrated in France.

Coaches: The bulk of the passenger carrying stock consisted of 28 1/2 feet long bogie open toast racks with awning roofs. In an endeavour to keep the unladen weight to a minimum (the coaches were designed for 48 sitting and 8 standing passengers) an interesting method had been adopted of constructing the longitudinal under frames of iron lattice girders. No weight details are available of these vehicles but by this method of construction they should have been comparatively light (albeit at the expense of the nerves of the painter who had to cope with the intricacies of the lattice work!). There was in addition a special saloon carriage for the use of the President of the Republic. This rather handsome little four wheel coach was fitted with a brake on one end platform and had longitudinal seats. Pete Harris has written an article on building this coach for this issue of the 'Mercury" and there is an accompanying 16 mm/1 ft scale drawing.

Wagons: Many of the various classes of standard Decauville wagons were also exhibited including 48-ton trucks (complete with gun). This was composed of four standard trucks grouped together to form two 16-wheel trucks. Each pair of trucks was coupled together by connecting frames, the ends of which passed through central pins of the trucks. These connecting frames were in their turn braced together and on the centre of each was mounted the carrying platform. A similar 36-ton wagon mounted on four 6-wheel trucks was also shown and had proved itself to be particularly useful in the construction of the Exhibition. All the conditions for working the trains had obviously been planned ahead in very great detail and were minutely laid down in the Decauville contract. Among other things this stipulated that every train must be fitted with a quick action brake. No details of vacuum or air brakes were shown on any rolling stock drawings so it must be assumed that the screw brakes on the locomotives was taken to be sufficient although further information on this point would be of interest. The railway was constructed under the supervision of Mr. M. Charton, assistant engineer of buildings at the Exhibition, who was also in charge of all the temporary railways connected with the Exhibition. The general management of the line was directed by Mr. M.G. Berges, Director General of the Exhibition.

Use of the railways during the construction of the Exhibition and the arrangement of the exhibits has already been mentioned and portable lines were laid throughout the grounds. Besides the trucks for heavy loads a travelling crane mounted on a 6-wheel truck and fitted with a screw brake was found to do a particularly useful job. The jib was mounted on a revolving platform of the truck deck and an interesting method of suspension was used to equalize the pressure on the wheels for almost any position of the jib.

Besides the railway itself Decauville had a display in the Agricultural Galleries where specimens of wagons used in forest industries, beetroot and sugar plantations were shown. Near the Eiffel Tower Station was a collection of military wagons, including the gun carrying truck, and there was also rolling stock for mines and earthworks, together with passenger carriages of various sorts. Contemporary accounts evidence the success of the railway at the Exhibition. Within a few days of opening it was noted that despite relatively poor initial attendances "the Decauville Railway is very largely patronized and it is certain that this enterprising constructor and concessionaire will reap a rich harvest from his contract with the Exhibition authorities". A month later the expense of running the line could be assessed. This was costing a total of £120 per day of which £40 was for wages, fuel, oil and stores, £40 for the depreciation of the permanent way and rolling stock and interest on capital, and £40 was put aside to cover the expenses later of closing up the tunnels and restoring road surfaces. In addition the French administration charged a tax for every thousand passengers carried. On some days nearly 4)0,000 were entering the Exhibition and the railway conveyed its millionth passenger within six weeks and earned during this period a gross revenue of £10,000 or approximately £240 per day. On this basis it was confidently anticipated that the gross revenue of the line during the six months of the Exhibition would exceed £70,000 since it was not felt likely that traffic would fall off. This would have required a total number of passengers over the six months of 7 million. In the event over 6 million people were carried and on the above figures the railway should have realized a profit of about £30,000 evidencing its very great success. Decauville were on the right (of) way to fame and fortune.

Gauge: 600m Maximum Train Length: 165 feet

Steepest Gradient: 1 in 40 for 300 feet

Fare: 25 centimes for any distance

Minimum Curve: radius 131 feet (on sidings reduced to 65 ft 7 ins) Frequency of Service: every 10 minutes from 09.00 hrs to closing time.

Maximum Speed: 10 mph (reduced to 2 mph on level crossings)

Track: the steel rail was of 19 lbs/yard riveted to dished steel sleepers spaced about two feet apart. Complete sections of track were riveted together into lengths of about 16 1/2 feet at the Petit-Bourg works and needed only to be fishplated together at the Exhibition site and then laid well embedded in ballast. This permanent way was designed to carry a working load of three tons per axle.

Rolling Stock: It was considered that fifteen locomotives and one hundred carriages would be sufficient to run the 180 trains per day and in addition a number of wagons were specially constructed to assist in the erection of that Exhibition.

Locomotives: Prior to the Exhibition about 70 locomotives had been 'built' by Decauville. For the Exhibition ten (one source says seven) compound locomotives on the Mallet system were built and the names given to these referred to various applications of the Decauville system of railways. For example the TURKESTAN referred to 60 miles of line constructed in 1882 for temporary purposes in building the Transcaspian Railway, the AFGANISTAN commemorated the elephant line already mentioned, the MASSOUAH was named after a large order given by the Italian Government during the Abyssinian campaign, the AUSTRALIA as a complement to the Australian sugar making companies, and the MADAGASCAR and HANOI refer to lines laid down by the French Government. In addition it was intended that five other locomotives were to be used consisting of the 0-4-0+0-4-OT Pechot-Bourdon type and standard 4 ton empty Tank types. However no firm evidence has come to light that those latter types were in fact used. The 75 hp Mallet was the standard engine being 'built' by the firm at the time. On a straight level track it was capable of hauling 280 ton and this fell to 17 tons by a 1 in 15 gradient. The first Decauville-built Mallet had been exhibited the previous year at the concours Regional de Laon where a 600 mm line had first been demonstrated in France.

Coaches: The bulk of the passenger carrying stock consisted of 28 1/2 feet long bogie open toast racks with awning roofs. In an endeavour to keep the unladen weight to a minimum (the coaches were designed for 48 sitting and 8 standing passengers) an interesting method had been adopted of constructing the longitudinal under frames of iron lattice girders. No weight details are available of these vehicles but by this method of construction they should have been comparatively light (albeit at the expense of the nerves of the painter who had to cope with the intricacies of the lattice work!). There was in addition a special saloon carriage for the use of the President of the Republic. This rather handsome little four wheel coach was fitted with a brake on one end platform and had longitudinal seats. Pete Harris has written an article on building this coach for this issue of the 'Mercury" and there is an accompanying 16 mm/1 ft scale drawing.

Wagons: Many of the various classes of standard Decauville wagons were also exhibited including 48-ton trucks (complete with gun). This was composed of four standard trucks grouped together to form two 16-wheel trucks. Each pair of trucks was coupled together by connecting frames, the ends of which passed through central pins of the trucks. These connecting frames were in their turn braced together and on the centre of each was mounted the carrying platform. A similar 36-ton wagon mounted on four 6-wheel trucks was also shown and had proved itself to be particularly useful in the construction of the Exhibition. All the conditions for working the trains had obviously been planned ahead in very great detail and were minutely laid down in the Decauville contract. Among other things this stipulated that every train must be fitted with a quick action brake. No details of vacuum or air brakes were shown on any rolling stock drawings so it must be assumed that the screw brakes on the locomotives was taken to be sufficient although further information on this point would be of interest. The railway was constructed under the supervision of Mr. M. Charton, assistant engineer of buildings at the Exhibition, who was also in charge of all the temporary railways connected with the Exhibition. The general management of the line was directed by Mr. M.G. Berges, Director General of the Exhibition.

Use of the railways during the construction of the Exhibition and the arrangement of the exhibits has already been mentioned and portable lines were laid throughout the grounds. Besides the trucks for heavy loads a travelling crane mounted on a 6-wheel truck and fitted with a screw brake was found to do a particularly useful job. The jib was mounted on a revolving platform of the truck deck and an interesting method of suspension was used to equalize the pressure on the wheels for almost any position of the jib.

Besides the railway itself Decauville had a display in the Agricultural Galleries where specimens of wagons used in forest industries, beetroot and sugar plantations were shown. Near the Eiffel Tower Station was a collection of military wagons, including the gun carrying truck, and there was also rolling stock for mines and earthworks, together with passenger carriages of various sorts. Contemporary accounts evidence the success of the railway at the Exhibition. Within a few days of opening it was noted that despite relatively poor initial attendances "the Decauville Railway is very largely patronized and it is certain that this enterprising constructor and concessionaire will reap a rich harvest from his contract with the Exhibition authorities". A month later the expense of running the line could be assessed. This was costing a total of £120 per day of which £40 was for wages, fuel, oil and stores, £40 for the depreciation of the permanent way and rolling stock and interest on capital, and £40 was put aside to cover the expenses later of closing up the tunnels and restoring road surfaces. In addition the French administration charged a tax for every thousand passengers carried. On some days nearly 4)0,000 were entering the Exhibition and the railway conveyed its millionth passenger within six weeks and earned during this period a gross revenue of £10,000 or approximately £240 per day. On this basis it was confidently anticipated that the gross revenue of the line during the six months of the Exhibition would exceed £70,000 since it was not felt likely that traffic would fall off. This would have required a total number of passengers over the six months of 7 million. In the event over 6 million people were carried and on the above figures the railway should have realized a profit of about £30,000 evidencing its very great success. Decauville were on the right (of) way to fame and fortune.