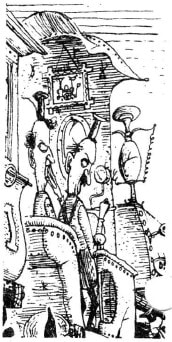

Trains by Emett.

TRAINS BY EMETT,

Photographed by CHARLES HEWITT

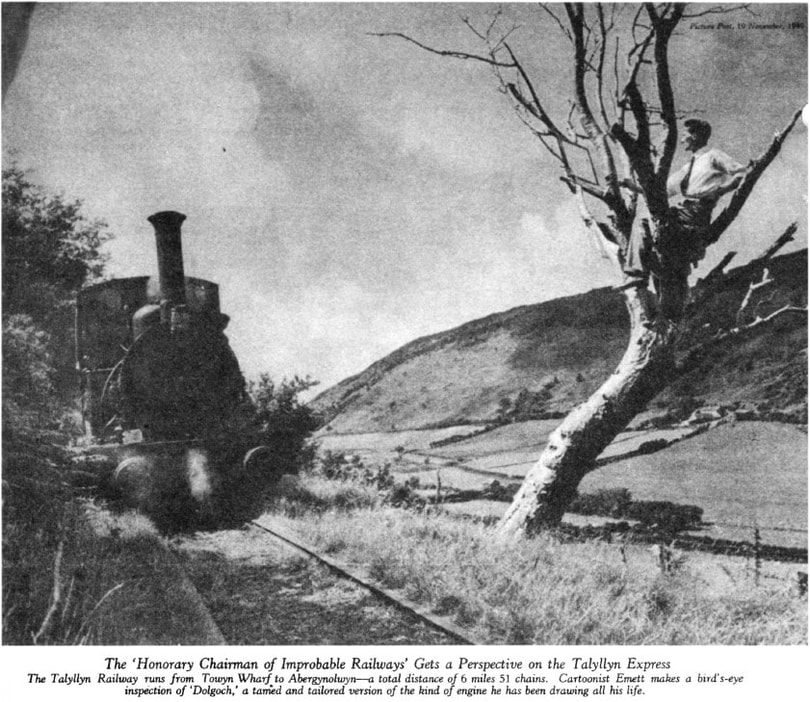

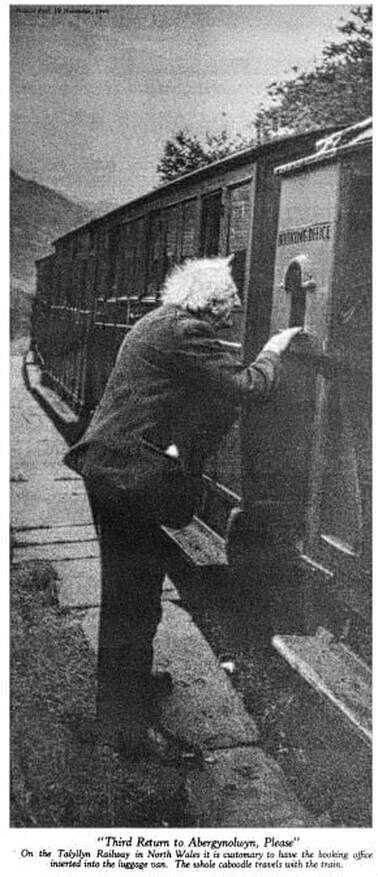

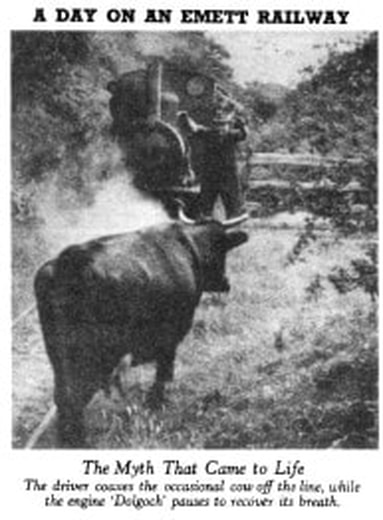

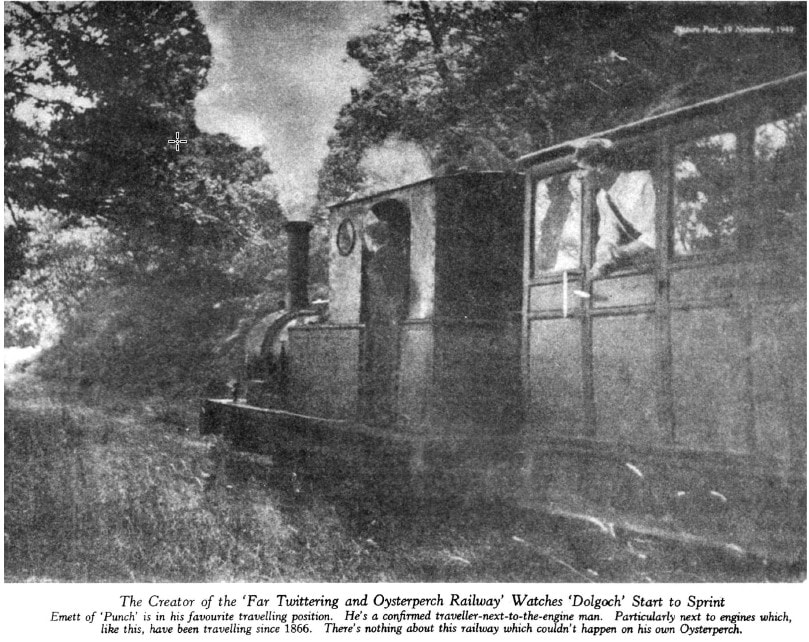

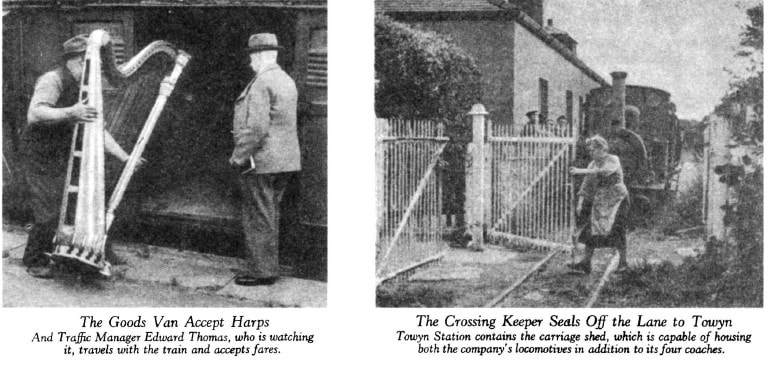

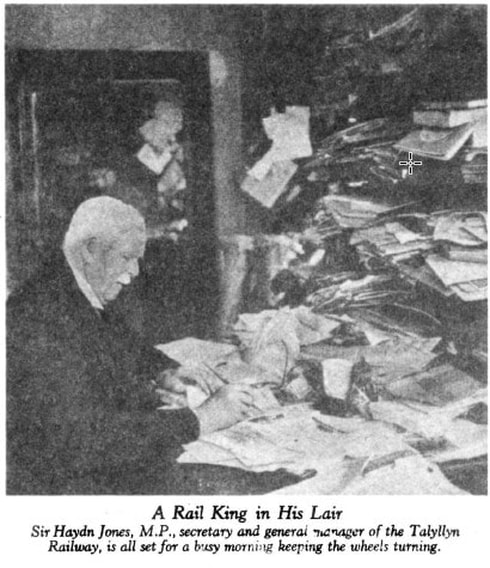

Emett of 'Punch,' creator of the 'Far Twittering and Oysterperch Railway' Ands, in North Wales,

something pleasingly like his own creation.

Photographed by CHARLES HEWITT

Emett of 'Punch,' creator of the 'Far Twittering and Oysterperch Railway' Ands, in North Wales,

something pleasingly like his own creation.

|

NO matter how obscure or eccentric your secret obsession may be—breeding newts, perhaps, or collecting old play-bills—there is probably, somewhere, a job waiting for you which am turn you into a professional. A man who had a lifelong fascination for the armourer's lost art, for example, now makes his living patching chain armour in the Tower of London; another had made a national name by digging up medieval cloth-seals, ancient jewellery and coins from the mud-flats round Wapping.

Rowland Emett differed from the vast army of schoolboy train obsessionists in that he carried his mania into adult life. Moreover, he appreciated that the engine which, travelling at a mere 20 miles an hour, knocked the luckless, Mr. Huskisson flying before a horrified audience at the opening of the Stockton to Darlington Railway over a century ago, had about it a romance and an absurdity which is |

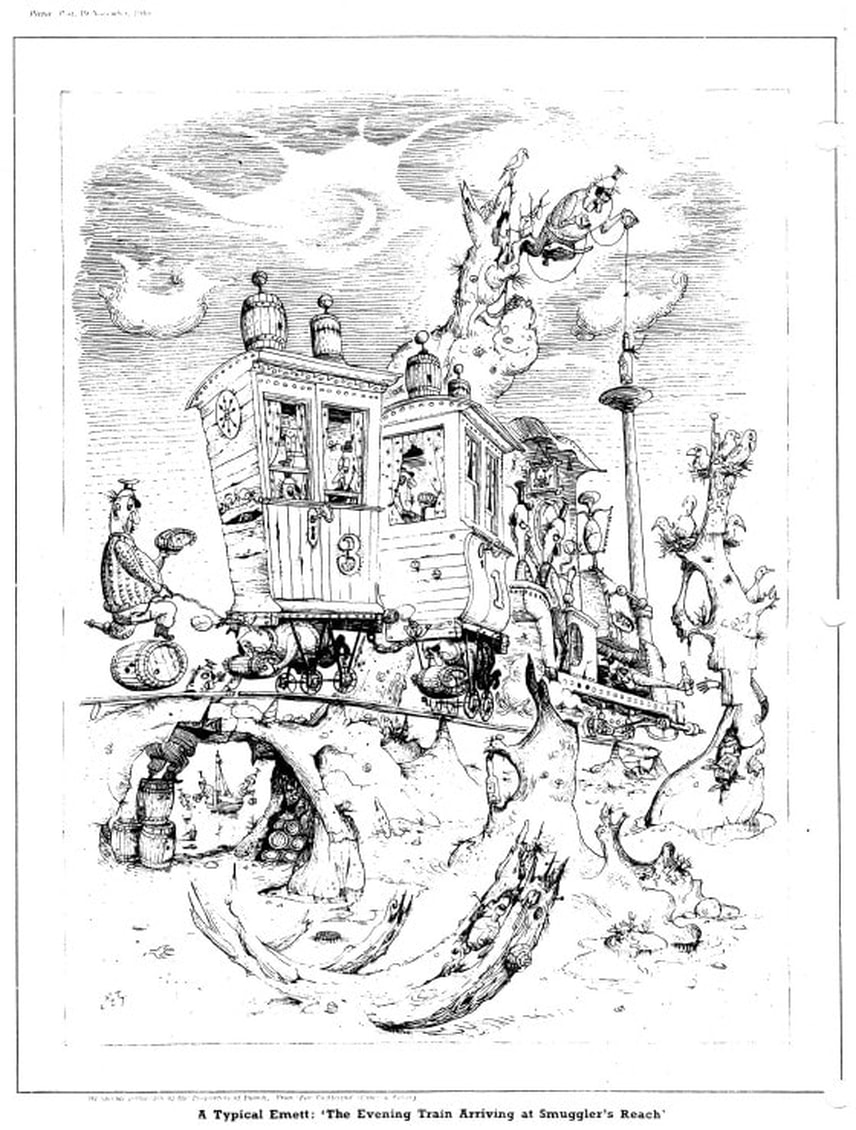

wholly lost in the age of streamlined Coronation Scots and Bristol Flyers. He therefore decided, with rare perception and independence, to follow the progress of the railway, not forwards, but backwards. But even this did not satisfy him; and before long he had traced its origins not only to their known starting point, but far beyond it, down a winding, dreamlike branch line. The weird and timeless locomotives he created were destined one day to become, to the British public, as much a reality as the uncharted sea where lurked the dreaded Shark, or the Land Where the Jumblies Live.

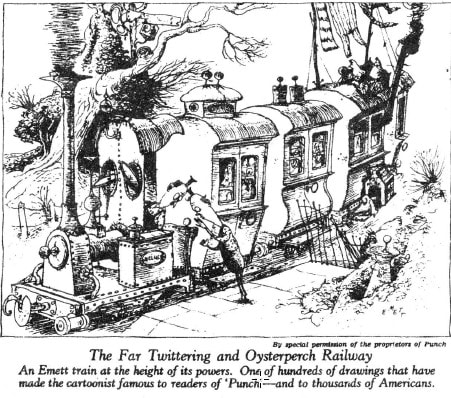

It was, of course, fortunate for the world that he could draw—indeed, he has exhibited his serious landscape paintings both at the Royal Academy and the R.B.A. Galleries. Yet for a time he never seriously expected anybody but himself to find anything funny about the wobbly, switchback excursions to Oysterperch, Far Twittering and district behind 'Nellie'—his original prototype engine—which he made in his mind or on odd bits of paper when the spirit moved him.

One day, however, he sent in to Punch a more or less orthodox joke cartoon about Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini. Punch sent it back. But on the rejection slip was a penciled postscript from the Editor saying that it was, nonetheless, ingenious and he should try again. Still he did not think it worthwhile trying them Arith `Nellie.' Instead, he sent them a number of straightforward cartoons in which the characters, though they tended to have spindly legs and Anglo-Indian moustaches or 'Aunt Agatha' hats, were only half-developed into the people we expect from him today. But this time Punch said "yes," and soon he had joined the ranks of their regular contributors. At last, with a good deal of diffidence, he offered them a full-blown `Nellie' drawing.

It was an instantaneous success. Within a few months people trying to describe some particularly *ill Hay-like branch line on which they had to travel in some remote district, found themselves saying, "Honestly, it was like one of those trains that man does in Punch." Another few months and they could supply the name. `Emett trains' had taken their place in the dynasty of Bateman colonels, George Belcher charwomen, Charles Grave bo'suns and the other great Punch clans. An R.A.F. pilot, returning from a sweep, would enter in his official report that he had met no enemy aircraft, but had seen and shot up `one Emett train' on his way home. From all over the world, particularly the Dominions and America, letters poured in to him with pictures and descriptions of outlying local railways—which his correspondents thought to be the nearest real-life approach to the Emett standard of antedeluvian absurdity. So that, with his bulging files and cutting-books, he must now be one of the greatest living experts on what might be called `locomotorfantaxia.'

It was, of course, fortunate for the world that he could draw—indeed, he has exhibited his serious landscape paintings both at the Royal Academy and the R.B.A. Galleries. Yet for a time he never seriously expected anybody but himself to find anything funny about the wobbly, switchback excursions to Oysterperch, Far Twittering and district behind 'Nellie'—his original prototype engine—which he made in his mind or on odd bits of paper when the spirit moved him.

One day, however, he sent in to Punch a more or less orthodox joke cartoon about Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini. Punch sent it back. But on the rejection slip was a penciled postscript from the Editor saying that it was, nonetheless, ingenious and he should try again. Still he did not think it worthwhile trying them Arith `Nellie.' Instead, he sent them a number of straightforward cartoons in which the characters, though they tended to have spindly legs and Anglo-Indian moustaches or 'Aunt Agatha' hats, were only half-developed into the people we expect from him today. But this time Punch said "yes," and soon he had joined the ranks of their regular contributors. At last, with a good deal of diffidence, he offered them a full-blown `Nellie' drawing.

It was an instantaneous success. Within a few months people trying to describe some particularly *ill Hay-like branch line on which they had to travel in some remote district, found themselves saying, "Honestly, it was like one of those trains that man does in Punch." Another few months and they could supply the name. `Emett trains' had taken their place in the dynasty of Bateman colonels, George Belcher charwomen, Charles Grave bo'suns and the other great Punch clans. An R.A.F. pilot, returning from a sweep, would enter in his official report that he had met no enemy aircraft, but had seen and shot up `one Emett train' on his way home. From all over the world, particularly the Dominions and America, letters poured in to him with pictures and descriptions of outlying local railways—which his correspondents thought to be the nearest real-life approach to the Emett standard of antedeluvian absurdity. So that, with his bulging files and cutting-books, he must now be one of the greatest living experts on what might be called `locomotorfantaxia.'

Since then, ingenious working models of Emett trains have been constructed by hobbyists in England, Australia and elsewhere. One of them, `The Antimacassar,' was televised with a commentary by Emett not long ago. He himself has made a Nellie,'which—since its 'boiler' is an old door-knob, —might not be expected to go very well. But a little technicality like this was nothing to the Emett master mind, and by concealing a flat boiler and a spirit lamp under the footplate, connected to an upright oscillating engine, which is hidden for'ard in the smoke-box, he was able to make it run for just eight minutes. Emett enthusiasts will be comforted to know that, though it runs on lines only five eighths of an inch apart, the chimney, made from a blowlamp nozzle, reaches 13 inches from the ground.

|

People have sometimes been inclined to compare Emett's creations with the elaborate baby-bathing, boot-cleaning or apple-core-extracting inventions of the late W. Heath Robinson, with their vast entanglements of knotted string, rolling-pin pulleys, and the rest. But, apart from the fact that Emett likewise runs much of his rolling-stock on empty barrels, sundial faces and anything else which comes into his head, there is little resemblance between them. Heath Robinson's studious, bulb-nosed operators still belong to this world, and his inventions, however grotesque, never enter the realm of pure fantasy. But Emett allows himself no such limits to his invention. He is a surrealist—but a surrealist who caters for children and grown-ups who like their fantasy straight.

Nor does the range of his appeal end there. His diligent, popeyed and benevolently dotty engineers and fishermen, peering at their watches, through telescopes or round the edge of a guard's van—but always peering—are the perfect holiday company for anyone whose life is normally lived in the competitive batter of business or |

professional life. One knows that at the end of a long evening with them at 'The Lobster Pot,' if one played one's cards well, one would at last crack through that crust of bewildered earnestness. And then, after giving vent to a long, nasal tuning note, they would break into a deafening and largely unintelligible song about Farmer Ragget's spotted cow. And his little gimcrack awnings, propped up with clothes props or lashed uncertainly between two skeleton trees, satisfy in us the ineradicable child instinct for rigging up unconvincing little wigwams out of chair-backs and overcoats.

Though Emett, officially 'Emett of Punch,' is under contract to them, and cannot draw for other magazines without a special dispensation, his books are selling furiously in the U.S.A. Their sales there will certainly be making another spurt since the New York Times got him to draw, as a two-page spread, his mind's eye conception of the famous Long Island Railway—and followed up with a request for another showing his idea of the city's waterfront. Thus, at a time when our more seriously run concerns are having a very bad time of it, The Great Ernest Railway is paying handsomely both in sterling and dollars.

And so—let reactionaries beware 1 For however much they may deplore it, the advocates of the coach-and-four must face the fact that a new chapter has been opened in the history of transport and, as his prospectus might say, "Mr. Emett's universally applauded iron horse"—or should one say "iron giraffe" ?--"is unquestionably here to stay."

Though Emett, officially 'Emett of Punch,' is under contract to them, and cannot draw for other magazines without a special dispensation, his books are selling furiously in the U.S.A. Their sales there will certainly be making another spurt since the New York Times got him to draw, as a two-page spread, his mind's eye conception of the famous Long Island Railway—and followed up with a request for another showing his idea of the city's waterfront. Thus, at a time when our more seriously run concerns are having a very bad time of it, The Great Ernest Railway is paying handsomely both in sterling and dollars.

And so—let reactionaries beware 1 For however much they may deplore it, the advocates of the coach-and-four must face the fact that a new chapter has been opened in the history of transport and, as his prospectus might say, "Mr. Emett's universally applauded iron horse"—or should one say "iron giraffe" ?--"is unquestionably here to stay."