As some of our readers may be of a nervous disposition, and in view of two mildly misleading mastheads elsewhere in this issue, the Editor thought it better to break it gently to you that the real subject of this article is well, er . . . CONTROVERSIAL. And the masthead is misleading too!

First of all, the country under discussion is located somewhat further south of Portmadoc than Boston Lodge, (actually France), and the means of propulsion being considered is not steam. But before we go any further, the drawing shows a proposed French atmospheric monorail, pre‑Lartigue, about which more in the next issue. The excellent drawing - by the way - is from the prolific pen of Roy Schofield.

" Sauterelles" was the somewhat contemptuous vernacular term used by the natives to describe the often rickety, frequently noisy, always bouncy and usually evil-smelling railcars or autorails which mushroomed in France in the 20's and 30's, lasted through the 40's (often powered by gasogene generators or gas bags "for the duration")and mostly expired in the 50's.

Since this journal is supposed to confine itself to the near 2ft gauges, we'll start with some 60cm gauge machines. By the 1920's, the internal combustion engine had developed considerably from the over engineered and temperamental pre-War machines in terms of both power to weight ratios and reliability. War has always been a good forcing ground for transport technology! Early petrol-mechanical transmissions tended to suffer from torque loss during gear changing, as well as over enthusiastic drivers. Witness the Superintendent of the Tramways de Tarn-et-Girande, where initially their railcars suffered more breakdowns than successful runs:

"The delays are due not so much to motor failure as to the fact that the driver, though willing and brave, does not yet understand his gears."

To overcome these -and other-problems a Monsieur Crochat patented in about 1920 a form of petrol-electric drive, known (unsurprisingly) as the Systke Crochat. The exact basis of the patent eludes me, as in the U.K. Messrs. Tillings Stevens had been building fleets of petrol-electric road lorries since the mid teens, the War Department finding them most reliable in the appalling front line conditions of the Great War. In Germany, the firm of Fross-Biissing had supplied a number of standard gauge road-rail convertible lorries for the use of the Austro-Hungarian military.

Anyway, there appear to have been between 6 and 8 autorails built for the 60cm gauge in France to the Systeme Crochat during the 1920's. Several others were built for both metre and standard - gauge lines.

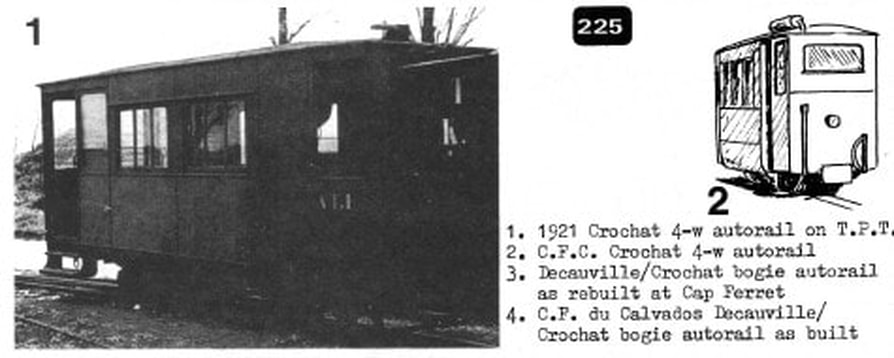

The first four cars appear to have been built by a firm using the Crochat name, but this cannot be stated with absolute certainty due to the perverse habit of French railcar operators of calling their machines by the name of the designer, the motor-maker, or the coach builder ‑ anything rather than the nominal manufacturer's. The very first machine was a four-wheeler built in 1921 for the Tramway de Pithiviers a Toury. It was single-ended and had a 30 h.p. four-cylinder Aster petrol engine powering a single 10 h p. electric motor; the final drive was via the front axle. The body was a straight-sided affair in wood with a domed roof, and from front to rear the accommodation comprised: driving cab, entered from the left side and containing the motor and electrical gear mounted transversely across the back; a 15-seat passenger compartment with longitudinal seats in slatted wood - the fifteenth being a flap-seat against the forward bulkhead; and a closed platform with sliding doors each side and officially capable of taking 15 standing passengers with four flap-seats (strapontins). Interior finish can best be described as "nicotine stain", the exterior being painted a dull green. The machine was numbered AT1 and remained in service until the passenger service was withdrawn in 1952. Since then it has served to transport permanent way gangs and, in season, agricultural workers going to and from the beet fields. It was still serviceable in 1964 and in virtually original condition.

First of all, the country under discussion is located somewhat further south of Portmadoc than Boston Lodge, (actually France), and the means of propulsion being considered is not steam. But before we go any further, the drawing shows a proposed French atmospheric monorail, pre‑Lartigue, about which more in the next issue. The excellent drawing - by the way - is from the prolific pen of Roy Schofield.

" Sauterelles" was the somewhat contemptuous vernacular term used by the natives to describe the often rickety, frequently noisy, always bouncy and usually evil-smelling railcars or autorails which mushroomed in France in the 20's and 30's, lasted through the 40's (often powered by gasogene generators or gas bags "for the duration")and mostly expired in the 50's.

Since this journal is supposed to confine itself to the near 2ft gauges, we'll start with some 60cm gauge machines. By the 1920's, the internal combustion engine had developed considerably from the over engineered and temperamental pre-War machines in terms of both power to weight ratios and reliability. War has always been a good forcing ground for transport technology! Early petrol-mechanical transmissions tended to suffer from torque loss during gear changing, as well as over enthusiastic drivers. Witness the Superintendent of the Tramways de Tarn-et-Girande, where initially their railcars suffered more breakdowns than successful runs:

"The delays are due not so much to motor failure as to the fact that the driver, though willing and brave, does not yet understand his gears."

To overcome these -and other-problems a Monsieur Crochat patented in about 1920 a form of petrol-electric drive, known (unsurprisingly) as the Systke Crochat. The exact basis of the patent eludes me, as in the U.K. Messrs. Tillings Stevens had been building fleets of petrol-electric road lorries since the mid teens, the War Department finding them most reliable in the appalling front line conditions of the Great War. In Germany, the firm of Fross-Biissing had supplied a number of standard gauge road-rail convertible lorries for the use of the Austro-Hungarian military.

Anyway, there appear to have been between 6 and 8 autorails built for the 60cm gauge in France to the Systeme Crochat during the 1920's. Several others were built for both metre and standard - gauge lines.

The first four cars appear to have been built by a firm using the Crochat name, but this cannot be stated with absolute certainty due to the perverse habit of French railcar operators of calling their machines by the name of the designer, the motor-maker, or the coach builder ‑ anything rather than the nominal manufacturer's. The very first machine was a four-wheeler built in 1921 for the Tramway de Pithiviers a Toury. It was single-ended and had a 30 h.p. four-cylinder Aster petrol engine powering a single 10 h p. electric motor; the final drive was via the front axle. The body was a straight-sided affair in wood with a domed roof, and from front to rear the accommodation comprised: driving cab, entered from the left side and containing the motor and electrical gear mounted transversely across the back; a 15-seat passenger compartment with longitudinal seats in slatted wood - the fifteenth being a flap-seat against the forward bulkhead; and a closed platform with sliding doors each side and officially capable of taking 15 standing passengers with four flap-seats (strapontins). Interior finish can best be described as "nicotine stain", the exterior being painted a dull green. The machine was numbered AT1 and remained in service until the passenger service was withdrawn in 1952. Since then it has served to transport permanent way gangs and, in season, agricultural workers going to and from the beet fields. It was still serviceable in 1964 and in virtually original condition.

Four years later, in 1925, three slightly improved versions of the T.P.T. design were delivered to the C.F. du Calvados, where they were numbered AU 1, 2, 3. They differed mainly in having two 10 h.p. electric motors instead of one, although they were still powered by the 30 h.p. Aster engine. They were double-ended, the arrangement being similar to that of the T.P.T. machine except that the main passenger compartment seated only 13 people on transverse seats; and there was a second driving position behind the entrance platform and reached from it. The bodywork was also slightly more elegant.

Apart from 1925-6, when they worked some through trains to the Bayeux section, and a short spell in 1932, they were used exclusively on the original section of line, from Caen to Dives and Luc-sur-Mer, where they ran most winter services and a few summer ones. They were not too popular on the latter work because their already small capacity included 15 standing passengers; there was no baggage space and they could only pull one or at the most two small trailers. In early days it appears that this was aggravated by the C.F.C. who made the seated section second class, so that third class passengers were compelled to stand. This arrangement was later altered to all third class and the cars ran until the withdrawal of all passengers at the end of the summer season in 1937. They were then stored at the Demi-Lune depot and appear to have been scrapped on the final closure. Like the T.P.T. car, they were fitted with Westinghouse air-brakes.

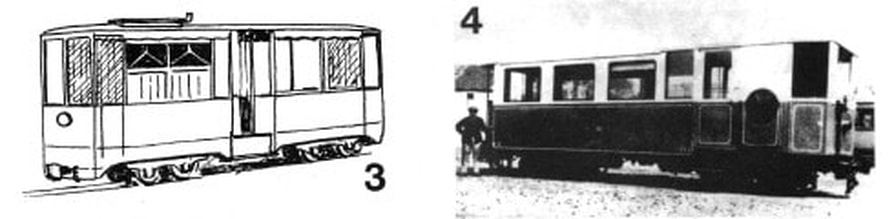

The remaining two - or four - cars are a little more mysterious. Jean Robert, in 'De Nice a Chamonix', states that in 1924 "two Decauville and two Crochat" bogie railcars were delivered to the Tramways de Savoie, a,Regie Departementale operating the 60cm gauge network around Chambery. But other sources record that, three years after the closure of this system at the beginning of 1933, "the two Decauville-Crochat railcars" were sold to the C.F.C. From available evidence it would appear that only two cars were built, being by Decauville using the Crochat system.

The cars were very advanced for their period. They were single enders, with metal-clad bodies and large windows, and from front to rear the accommodation comprised: driving cab, with the motor/generator group arranged as on the four-wheelers; a windowed luggage compartment with sliding doors on each side; a 19-seat passenger compartment; and a small balcony giving access to the passenger compartment and deemed capable of holding four standing passengers. They were more powerful than their predecessors, with a 35 h.p. Aster engine driving four electric motors, and attained 60 km.p.h. on trials. In service on the C.F.C. they regularly pulled one or two bogie trailers specially equipped with Westinghouse brakes, electric lighting and a heating system worked off the railcar's exhaust.

Apart from 1925-6, when they worked some through trains to the Bayeux section, and a short spell in 1932, they were used exclusively on the original section of line, from Caen to Dives and Luc-sur-Mer, where they ran most winter services and a few summer ones. They were not too popular on the latter work because their already small capacity included 15 standing passengers; there was no baggage space and they could only pull one or at the most two small trailers. In early days it appears that this was aggravated by the C.F.C. who made the seated section second class, so that third class passengers were compelled to stand. This arrangement was later altered to all third class and the cars ran until the withdrawal of all passengers at the end of the summer season in 1937. They were then stored at the Demi-Lune depot and appear to have been scrapped on the final closure. Like the T.P.T. car, they were fitted with Westinghouse air-brakes.

The remaining two - or four - cars are a little more mysterious. Jean Robert, in 'De Nice a Chamonix', states that in 1924 "two Decauville and two Crochat" bogie railcars were delivered to the Tramways de Savoie, a,Regie Departementale operating the 60cm gauge network around Chambery. But other sources record that, three years after the closure of this system at the beginning of 1933, "the two Decauville-Crochat railcars" were sold to the C.F.C. From available evidence it would appear that only two cars were built, being by Decauville using the Crochat system.

The cars were very advanced for their period. They were single enders, with metal-clad bodies and large windows, and from front to rear the accommodation comprised: driving cab, with the motor/generator group arranged as on the four-wheelers; a windowed luggage compartment with sliding doors on each side; a 19-seat passenger compartment; and a small balcony giving access to the passenger compartment and deemed capable of holding four standing passengers. They were more powerful than their predecessors, with a 35 h.p. Aster engine driving four electric motors, and attained 60 km.p.h. on trials. In service on the C.F.C. they regularly pulled one or two bogie trailers specially equipped with Westinghouse brakes, electric lighting and a heating system worked off the railcar's exhaust.

These cars, carrying their old numbers DC 11, 12, were purchased in 1936 by the Departement du Calvados, and put into service by the C.F.C. on the Caen h Luc line, by that time the only branch carrying a regular passenger service. The turntables had to be specially enlarged to take them, as the single driving position necessitated their being turned at the end of each run. When passenger services ceased they were sold to the Departement du Loiret for the Tramway de Pithiviers a Toury, on which they worked until the cessation of passenger services in 1952. It appears probable that one was cannibalised to keep the other going and in 1955 one complete car and certain parts of the other were sold to the Tramway de Cap Ferret at Arcachon; the remaining body was thriftily converted by the Loiret Departement into a road laboratory trailer for their Ponts-et-Chaussees section and may still exist. The car which went to Arcachon was rebuilt with a new semi-open body having two driving positions, but seats for only 12 passengers with a theoretical 19 standing. In this form it was unsuccessful, with the result that it was sold to the C.F.T.M., who rebuilt it with a larger body, at the same time substituting a diesel engine for the elderly Aster petrol one.